Howard Head was a tall man with a shiny bald head and ears that stuck out from his head, as though he were pushing them forward to better hear someone. He was also a famous man. At least, his skis and tennis racquets were famous. But sitting in the Archive Center at the National Museum of American History, I began to trace a different story. Along with thousands of papers detailing a happy, creative, and hardworking man, I began to develop a more corporate narrative that departed from the endless articles praising this man.

Head did not begin his career in the sportswear industry. Rather, he was a Harvard-educated engineer, who built his skis based on (admittedly) innovative military technology – his method came from some of the most deadly warplanes of all time. His papers reveal this far more serious man, who understood mechanical and chemical engineering and who felt comfortable working with global corporations. So, what happens when we tell a story of Howard Head the businessman, not just the inventor?

It is not a secret. The United States thrived off World War II’s wartime innovation. And skis are not the only outdoor technology to benefit from it. New ski bindings, GORE-TEX, nylon and so many others were first invented for war. But skis are a little different. These weren’t invented to keep soldiers safe and warm – they came from technology meant to search and destroy.

So, how can we balance these opposing stories of Howard Head, the fanciful inventor, and the wartime engineer? What does it mean for the stories we tell about skiing’s past? And what does it mean for the soul of skiing?

(Elf.Agency)

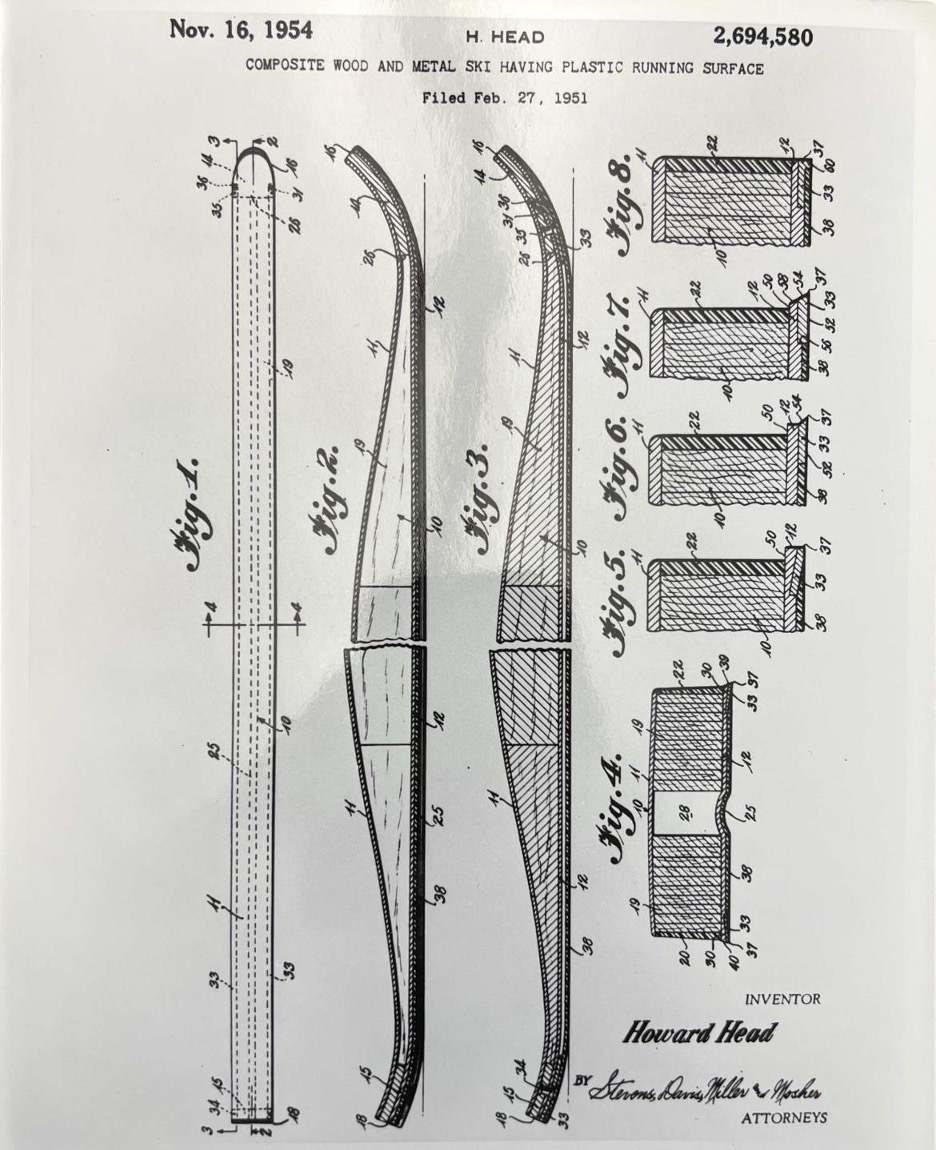

Head designed the first popular metal ski. His “legendary aluminum sandwich ski,” one biographer raved, “played a critical role in transforming a small elitist sport into the booming recreational ski industry.” Easy to edge, pleasant to turn, comparatively light, and difficult to break, by the standards of the forties and fifties the original Head ski effortlessly carved into the snow. It didn’t twist under pressure, and its lightness let it float. It stands to reason they were a revelation.

The stories I found in his personal papers described an affable and spirited man – and there are many stories to back it up. For the most part, these letters came from a collecting initiative by the museum. In 1989, the Smithsonian Institute began collecting Head’s skis and papers. But Head hadn’t preserved all his models. So, the museum advertised. They asked for skis and stories from anyone willing to share. Enthusiastically, people replied in droves. They sent in their ski models and shared their stories. For friends and strangers alike, it was a chance to reminisce about their memories, about the good old days of skiing.

Head was still alive when the project started and seems to have reached out to old friends. Cliff Taylor, a longtime ski instructor, responded with an amusing tale describing his harrowing journey down Tuckerman’s Ravine in 1948.

There was a light chuckle hidden in his words, as if you could see his smile as he reminisced with his old friend. Setting the scene, he remembered his steep ascent up Mt. Washington. Meanwhile, Howard Head watched, sitting comfortably at the bottom. Then, Taylor spun his yarn.

“I proceed to put my skis on, and proceeded to pick up speed before dropping over the overhanging lip of the Ravine. My plan was to make 4 giant slalom turns, but after the forty-foot drop off of the lip, my speed was so great that I never got a chance to make even a second turn… You were elated and so was I, because the 1st Head Skis proved to have good edge control at high speeds” (emphasis original).

There is an irony here. A subtle roast lost to those who didn’t know Head. He may have been a ski innovator, but at the time Head was a novice skier. He only made his first turns the year before. In fact, the ski came from his frustration. He didn’t like that he was bad at the sport, and like all good athletes blamed his equipment. Until later years, he was by all accounts still a mediocre skier in the late forties. Bluntly, Head lacked the finesse needed to test the skis.

Finding a short autobiography in another folder, Taylor’s story went from charming to comical. In 1947, it turns out, Head went to Stowe, Vermont for the skis first ever on-snow test. Even with the tests,” he remarked, “every ski broke before the week was over.” Needless to say, it was not the best showing.

To his luck, the snow was variable, meaning he tested them in various conditions. Over the course of the week, the skis took on fresh snow and breakable crusts, crunchy eastern ice and ragged moguls. The skis may have broken, but they still received good reviews from the instructors who tested the skis. It least that is how he remembered it forty years later. The skiers may have felt differently when the skis split under their feet. Regardless, we can only assume Taylor, who lived in the region, knew how dangerous the test run truly was.

People who never knew Head sang his praise. In a letter accompanying his pair of 1957 Head Masters, Howard Siegle wrote to the National Museum of American History thankfully exclaiming that (in his view), “we all owe an unmeasurable debt to the foresight and inventive genius of Howard Head.”

Siegle wasn’t Head’s only fan. At the Archive Center, Box 13 is filled with folder after folder of people who wrote in, hoping the museum would choose their skis for the collection. It seemed a small space in which they could attach themselves to one of their ski hero, even if it was only through a simple piece of equipment. Often calling it an honor, they seemed to feel that even if their names went unmentioned, their passion for skiing might continue onwards, tied to the archive of skiing’s past. With them, the potential donators tried to convince the collectors, writing their thoughts and feelings about the skis – they were unanimously good.

These letters, the essays written, and the exhibits that celebrated him were all well deserved. But the history of the technology, rather than the mythological man, tells a different story. One that is far more uncomfortable, because it ties the most important improvement in ski technology’s history to the mechanical and chemical technologies from World War II that were developed to kill large numbers of people – quickly.

Head’s story usually starts after the war. In 1947, Howard Head, the founder, and creator of Head Skis quit his mid-level position at Glen L. Martin Company, an airplane manufacturer to make skis. Usually, these stories explain that he was a riveter (like Rosie). Ski writers describe the man as a “lifelong tinkerer.” The term is never said, but the implication is clear, these stories imply that he was just another working-class fellow. Even the finding aid to the Howard Head Papers embraces these keywords to carefully tie the man to a certain class – a class that matches the can-do attitude of the iconic ski bum.

This cliche is common throughout ski history, where upper-middle-class and upper-class industry members are sold as “down-to-earth” and relatable, lest someone confuse them with the wealthy skiers who dominate the industry. But, at least with regards to Head, the claim quickly disintegrates with only a cursory look through his papers.

Combing through the Howard Head Papers, it is clear that Head was anything but a “tinkerer,” a simple riveter, or working class. Rather, he was the son of a Philadelphia doctor, the product of elite private education, and an engineer with a degree from Harvard. With this pedigree, he certainly was above the position of riveter. Instead, he overlooked significant portions of the development and manufacturing process at the Martin L. Glen Baltimore plant. As he described it at the time, his job required “a technical familiarity with all parts and features of an airplane.”

Head’s voice is sometimes hard to parse in his early letters. In part, this reflects the fact that he mostly saved business-related correspondence. It turns out letters related to engineering, investment, and marketing are not where he embraced his inner novelist. (That drive didn’t come until old age.) Instead, the language was gray, terse, formal, and (of course) businesslike. Yet the cheerless prose offers a clear window into the development of skis as a business – not as a hobby turned profession. And through them, we can see what was actually happening at the time, not simply his and others’ fond memories from a half-century later.

Head was part of the large-scale war effort to build and improve warplanes at Glen L. Martin, which was one of the most important – and easily one of the most destructive – manufacturers of the time. The company was reasonably well known. Along with being featured in the famous propaganda film Bomber, the company designed and built the famed B-26 Marauder, the Boeing B-29 Superfortress, as well as the Silverplate, which was used to drop the “Little Boy” and the “Fat Man” on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In total, the company made over 2,000 planes throughout the war, received more value in government contracts than all but thirteen other corporations, and due to the nuclear bombs were directly related to the two most deadly attacks in world history.

Part of Glen L. Martin’s unique technology was a technique that used a honeycomb structure to create strong wings with minimum materials – in the process strengthening the plane without increasing the weight. They then bound the wings together through a process involving high pressure and high heat, in a process reducing the drag created by rivets. While the planes used aluminum honeycomb designs in the wings, Head adopted this same model for skis, though he choose to use lightweight plywood. (The use of wood was also used on the interior of planes for floors and walls.) Head then played metal around this airy frame, using the same seeling method as Glen L. Martin. Much as the lack of rivets reduced drag, the lack of rivets, screws, or nails mean that the bottom of the ski could remain flat, and slide evenly over the snow.

Head, admittedly, was not the only one to use aircraft technology to make skis. While he was the most successful, both Tey Manufacturers (who also invented the first snowmaking machine) and Vought Aircraft Corporation, also used wartime aviation technologies to make metal skis. Meanwhile, Dow Chemical (who also invented STYROFOAM® during the war) created a single-piece magnesium-based metal ski, based on a development process that was once again designed for airplane wings.(Magnesium would late play a key role in other companies’ forays into metal skis.)

Howard Head cannot (and should not) be held responsible for the development of these technologies. He did not invent them, and expecting him to refuse both services and work in a war-time factory would be an unrealistic expectation of someone living at the time. Yet, he did profit off it. And many of us reap the benefits of this technology.

Studying technology moves us away from romanticized visions of skiers’ encounters with untouched powder and pristine wilderness. Deep dives like this also highlight how skiing was not simply founded off the back of perceived war heroes like Pete Seibert (who founded Vail). Rather, the role of the military in skiing is far more violent.

The technological side of skiing was developed by ambitious engineers, from highly educated backgrounds, who were most often associated with the founding years of the military-industrial complex. Stories like these suggest that the nostalgic “mom & pop” ski areas were not the central drivers in the rise of skiing. Whether talking about Sun Valley, Aspen, Stowe, or Whiteface (all founded by the rich and famous with the backing of corporate entities), the development of skis, or the production of snow machines, skiing’s history is much more industrial than common memory suggests.

Centering the war-time technology skiing relied on, and highlighting the death these technologies wrought, doesn’t serve the nostalgic narrative that many others have traced. But, it does hint that maybe skiing’s declensionist narrative is misplaced. It is not that skiing turned corporate in the 1970s and 1980s. Rather, people just finally noticed.