In 1938, in the densely wooded forests of the Coconino National Forest, the Flagstaff, Arizona ski team opened a ski area at the base of Humphrey Peak. Cut into the middle of a mixed Birch-Pine forest, the ski hill, at the time, may have been the southernmost ski area in the country. And it marked an early point in the surprisingly strong ski culture that has emerged in the arid southwest. Humphrey Peak’s prodigious winter weather was only possible due to its towering height of 12,637 feet. Nevertheless, much like other ski hills of the time, Arizona Snowbowl remained little more than a lodge and rope tow until after World War II. But, in the early years, it did its job – allowing for the ski team to train, and for a few local enthusiasts to indoctrinate themselves into the still-new sport of Alpine skiing.

Two years earlier, in 1936, the first large-scale American resort opened in Sun Valley, Idaho. Sun Valley is one (of a few) origin stories for the American ski industry. Architectural historian Margaret Smith has written that despite being buried deep in Idaho’s wilderness “urbanity…exuded” from the resort. The Lodge at Sun Valley was luxurious. In a Union Pacific Railroad brochure, the new ski resort was described as a place where “civilization outposts meet a vast wilderness of mountain, forests, lakes, and streams,” continuing that the ski area had “the most modern and luxurious accommodations possible.” Costing $1.5 million, the lodge had over 200 rooms, and an entire wing dedicated to entertainment, public dining-rooms, and even shopping. Furthermore, the owner stuffed the lodge with New York City’s and Hollywood’s richest and famous, adding a cultural cache to the resort from the get-go. The building and the resort, in turn, eschewed the traditional western motifs of most resort architecture in the Rocky Mountains and the Sierra Nevadas, which tended to highlight natural opulence. Interestingly, the chief architect Gilbert Stanley Underwood had spent the previous years building lodges, such as the rustic Ahwahnee Hotel at Yosemite for the National Park Service. As a result, Sun Valley proved to be an about-turn for the architect most well-known for building with the surrounding environments rather than in contrast to them.

Sun Valley was financed and owned by railroad tycoon and politician Averell Harriman. Harriman not only had a special vision, he had the monetary means to create it. However, for the ski team in the small city of Flagstaff, building a high-end modern resort was not an option. Although no records specify how the decision was made, images suggest that the first lodge was influenced by the stylistic standards of the National Park Service and the Civilian Conservation Corps. The National Park Service, which was inaugurated in 1916, had guidelines dictating that buildings should be “rustic structures” that use local stone and wood, along with minimal ornamentation, to blend with their natural surroundings. Although few ski hills were on National Park Lands — more commonly slopes were cut in national and state forests — at least for the time, the rustic park-style proved more popular than Sun Valley’s modernism. Perhaps the two most famous of these are the small warming hut at Mount Mansfield (now Stowe, Vermont) and the iconic Timberline Lodge (on Mount Hood in Oregon).

The first lodge at Snowbowl was quite basic. Built within a grove of birch trees, the rustic log-cabin lodge fit seamlessly into the mountain-scape. For skiing, log cabins took on a double meaning. The design mimicked an idealized version of an American settler building a simple homestead in the hills. The image of the log cabin was a clear and readable symbol in American culture. The homage to the frontier would have been unmissable. However, log cabins are also a deep and persistent part of Scandinavian architecture. Skiing’s roots are in Scandinavian – and particularly Norwegian – culture, but the log cabin also likely derived from Swedish settlers in the 17th century. In a region with little Scandinavian immigration, it is not clear if Snowbowl was tied directly to the Norwegian tradition of skiing. Nevertheless, names such as Alf Engen (Alta) and Carl Howelsen (Steamboat Springs) — among many others — were already nationally famous for their role in bringing skiing to the United States. As a result, the American frontier and the Scandinavian ski cabin merged to call back to two geographically distinct histories. The large-scale modern lodge at Sun Valley brought to mind the idea of the increasingly modern and exclusive Alps. In contrast, smaller rustic lodges like Snowbowl’s (intentionally or unintentionally) pulled skiers minds back to an imagined history that conglomerated the sport’s national origin in Norway with America’s historical process of imperial expansion.

By the early 1940s, with World War II in full swing, Snowbowl all but shut down. In 1946, California businessman Al Grossmoen bought the ski area. He expanded the resort to include multiple rope tows and Poma-lifts. But he also chose to replace the cabin with a new lodge. The new Agassiz Lodge, like the first, was not built by a professional architect. Grossmoen, who designed it himself, likely brought ideas about ski architecture from California, where he had previously lived, to Arizona. Although a much smaller scale, the new lodge at Snowbowl was reminiscent of the larger base lodge built by William Wurster at Sugar Bowl in California, around Lake Tahoe. According to Smith, Sugar Bowl’s lodge was a “modern ‘ski shack’ evocative of vernacular mining structures in the region.”9 Built with a sturdy slanted roof, the Agassiz Lodge was, like the lodge at Sugar Bowl, built so that heavy snowfalls could slide off the back of the building. This design had two benefits. First, it created a dramatically large and unshaded window out of which people in the lodge could watch the slopes while warming up and eating lunch. Second, by pushing snow to only one side of the building, the roof protected the deck from roof-avalanches. This both saved ski-area staff from shoveling extra snow off the deck, while also protecting guests from potentially deadly snow slides — although deaths from roof-avalanches are exceptionally rare. The openness of the lodge to the ski slopes, along with the relatively closed-off nature of the road-facing side of the building, meant that unlike the original lodge, which pulled people equally into the slopes and the forest, this pulled the slopes into the building, allowing spectators in the lodge to in a sense take part in skiing.

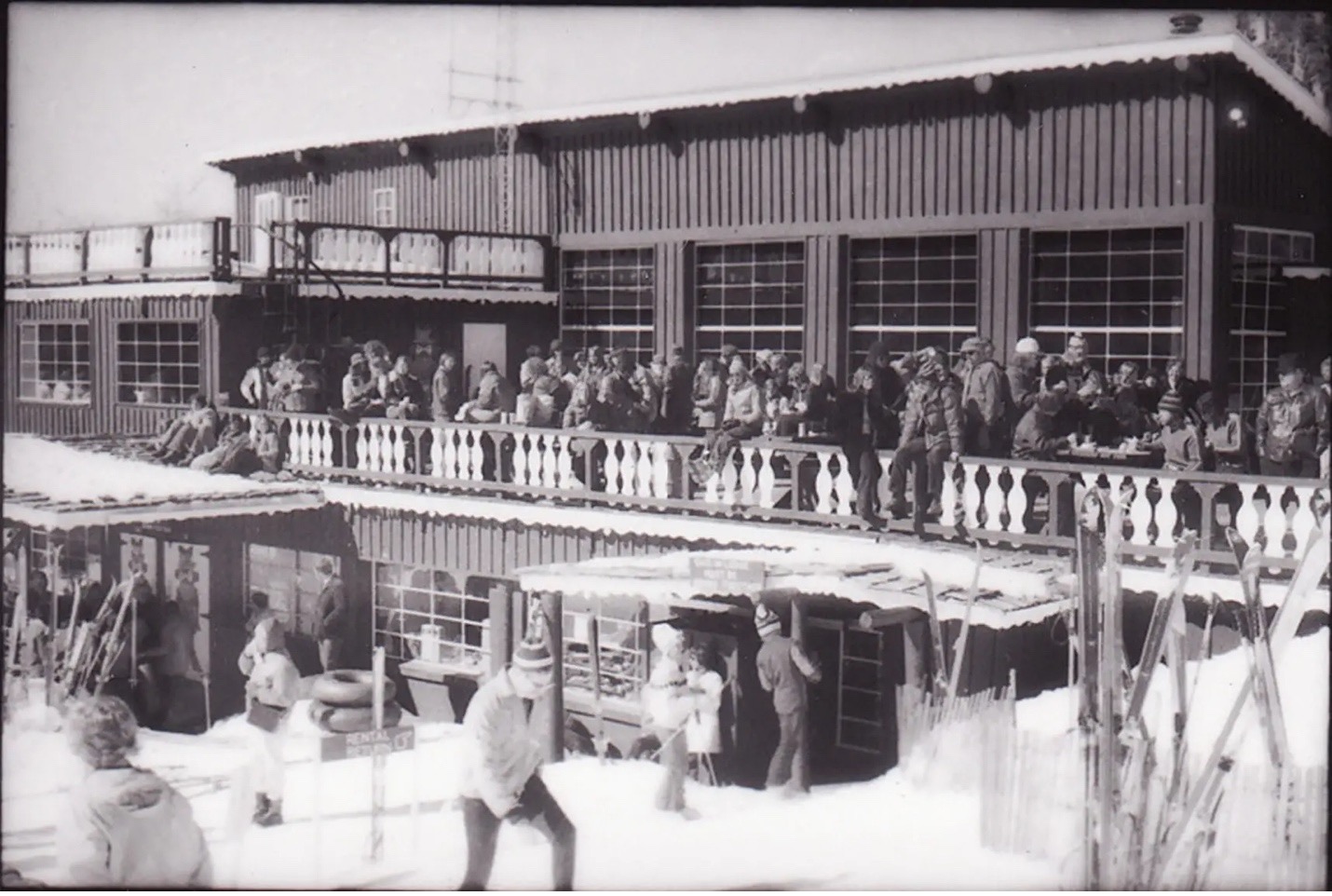

In addition to referencing California mining culture, the lodge also used subtle ornamentation to tie the building to other ski styles. For instance, the exposed timbered cross-beams visible under the roof harkened back to the rustic appeal of the older lodge. Meanwhile the white balusters on a brown building inverted a traditional Tyrolean color palate, hinting at Alpine skiing’s heritage in Tyrol — a move that intentionally or unintentionally revealed the increased understanding of Nordic and Alpine skiing as distinct sports. As a result, the lodges spoke to a number of different themes. It spoke to California mining history, the appeal of European ski culture, and the desire of people to watch people on the slopes. However, at the same time, the lodge itself was increasingly divorced from the environment around it. Making its conglomeration of styles somewhat out of place in northern Arizona.

While the lodge continued to be updated periodically, infrastructural improvements were more often functional in intention, than they were aesthetic. Nevertheless, these changes provided new meanings to both the building and slopes. For instance, while more famous resorts such as Sun Valley, Alta, Vail, and Mt. Mansfield (now Stowe) all boasted chairlifts as early as 1950, Snowbowl waited until 1960 to purchase their first. The chairlift, as well as the early ground lifts changed how quickly people could move up the slope, they also changed the mountain as ski-scape. The ski hill can be better understood if split into three imperfect parts – the bowl, the ridgeline, and the fall line. The natural bowl at the top funnels down into Logjam Trail (#8). Although Logjam is marked as a trail, it is unlikely that the space below the bowl was cut. Rather, Logjam may have been the natural runout of avalanches . The bowl, due to its steepness, has a number of avalanche paths. The dramatic force of the snow sliding down the mountain would have naturally prevented tree growth in the area. Part two is Thunderbird Trail (#7). This ridgeline was cut to allow skiers to traverse the ridge providing multiple paths into the gully. While ridgeline runs are not uncommon at ski areas, it is seems that Thunderbird was cut to give increased access to the mountain by working with its natural landscape. Finally, there are the various cut runs, zigzagging down towards the gully. (The gully itself acted as a funnel to bring skiers back to the base lodge where the lifts were located.)

Ski maps, rather than showing the topography of the mountain, are intended to make runs easier to follow. So, it is difficult to know precisely why runs where cut how they were. But the earliest runs were likely cut narrow and intentionally curving to provide a uniqueness to each trail. (This was later changed on many mountains throughout the country to better accommodate grooming and snowmaking pipelines.) In contrast to these runs, the Agassiz Double Chair (later replaced by a triple chair and then a gondola) cut a new type of line through the mountain. Pomalifts and rope tows worked best when facing directly up a fall line. In contrast, the chairlift was designed to find the most direct route to the top of the trail, cutting a diagonal path across slopes otherwise curated to maximize the natural contours of the mountains. The newness of this can be seen by how the lift cuts across several pre-existing slopes.

The addition of the chairlift in 1960, along with a second in 1988, not only changed the relatively natural landscape of the mountain, it also changed the relationship between the lodge and the slopes it looked onto. While mechanization was not new to skiing, the chairlift imposed its presence on the mountain in a different way. If sitting in the lodge, the chairlift could have either of two effects. Some may have seen it as an imposition onto an imagined natural landscape, while others may have viewed the lift as an object of interest itself that not only revealed, but perhaps celebrated, the sharp contrast between modernist technology and what some point to as a more primitive experience of sliding down a snowy mountain on wooden (and increasingly metal) skis.

Snowbowl is in many ways unremarkable. As a result, it represents an almost vernacular form of ski architecture – if such a thing can be said to exist. Rather than focusing on Aspen, Sun Valley, of Killington, exploring a resort that followed trends, rather than setting them, reveals what movements most broadly drove change within the ski industry. Snowbowl suggests that ski area design can be split into three separate forms. The first highlighted skiing as a natural part of the landscape. The second began to interrogate the role of the spectator and the relationship between the interior of lodges with the exterior mountain where people skied. Finally, the third form highlighted skiing as both a natural (or primitive) and a natural endeavor. Exploring thee three stages, Snowbowl demonstrates how many ski resorts constantly and consistently remade, repurposed, and re-paired buildings and landscapes to provide thoughtful and intentional aesthetics for their skiing clientele. In the process, these changes changed the meaning of skiing for those involved.

A lesson plan using some of these images is available here.